-

PLUS

Mobils stora guide till Apple Intelligence i Iphone

-

PLUS

Krönika: Mobiltillverkare för första gången, igen

-

PLUS

11 tips: Google-appen som kan mycket mer än du tror

-

PLUS

Krönika: Google är bra på gratis men usla på att ta betalt

-

PLUS

Så kan Xiaomi-telefonen bli Mac-datorns och Iphones bästa vän

-

PLUS

Chromecast-problemen visar hur svårt det är att lita på Google och andra jättar

-

PLUS

Passkeys: Därför behöver du veta mer om dem

-

PLUS

Krönika: Lärdomar från MWC 2025 – röststyrning är AI:s värsta fiende

-

PLUS

Fördjupning: Tankar och teknik bakom kamerorna i Samsung Galaxy S25

-

PLUS

Mobil svarar om Telenor-problem, seniorklocka, Airtag-konkurrenter och mer utrymme i Google Foto

Gästkrönika

Så planerar Xiaomi att erövra världen

Xiaomis ambitioner sträcker sig långt bortom smartphone-tillverkning, menar Michael Vakulenko och Elizabeth Woyke.

Apple skapade den första revolutionen på telefonmarknaden genom att ta smarta telefoner till massmarknaden. Google står för den andra revolutionen med Android, en plattform som gjort det möjligt för andra tillverkare att ge sig in på smartphone-marknaden. Xiaomi kan nu vara på väg att skapa den tredje revolutionen. Men hur kan smartphone-tillverkare konkurrera med Xiaomis innovativa affärsmodell?

Det är frågan som Michael Valulenko, strategidirektör på analysföretaget Vision Mobile samt Elizabeth Woyke, författaren av kritikerrosade boken ”The Smartphone: Anatomy of an Industry” och tidigare skribent på Forbes, Business Week och Time Magazine, svarar på i artikeln som Mobilbusiness exklusivt publicerar i sin helhet i Sverige.

Obs! Artikeln är på engelska.

How Smartphone Makers Can Compete With Xiaomi’s Disruptive Business Model

Michael Vakulenko and Elizabeth Woyke

If you haven’t been paying attention to the rise of Xiaomi, the China-based smartphone start-up with huge ambitions, you should start. Xiaomi only sells phones in Asia right now, but its innovative business model – which involves selling stylish, capable phones in limited quantities online at low cost and fostering a highly devoted community of users – is ushering in a third shift in the mobile market, like Apple and Google before it.

A FLUCTUATING MARKET

Mobile phones are a market in constant flux. Mobile technology is constantly changing and the industry’s business models are continuously evolving. In terms of major shifts, the mobile phone market has experienced two thus far. The first was in 2007 when Apple launched the iPhone, which took mobile computing mainstream. This disruption created the modern smartphone market. The industry’s second shift came in 2010 when handset makers began adopting Google’s Android operating system. Google’s practice of distributing Android free of charge enabled smartphone makers to reduce their product development costs and establish a huge, hypercompetitive smartphone market. How huge?

Eight out of 10 of all smartphones shipped in 2014 -- a quantity of more than one billion phones -- were Android phones, according to market researcher IDC.

Now we are on the verge of a third shift in the mobile phone market, led by Xiaomi. In the short time since Xiaomi released its first smartphone in August 2011, the start-up has become the world’s third-largest smartphone maker and China’s top smartphone vendor, according to IDC. Xiaomi has also attracted a USD 45 billion valuation – making it the world’s most highly valued tech start-up -- and heaps of media praise.

REPLICATING THE XIAOMI RECIPE

Impressed by Xiaomi’s rapid growth, other smartphone companies have started copying aspects of its business strategy. Huawei, for example, opened a direct-to-consumer online shop for its smartphones and other gadgets in June 2014. Huawei has been promoting the site, which targets U.S. consumers, with social media marketing. Lenovo is planning to launch an online brand called ShenQi in April that will sell smartphones directly to Chinese consumers instead of through wireless carriers. Lenovo views this strategy as “going face-to-face” with Xiaomi, according to a recent Bloomberg article.

It is no surprise that smartphone companies are trying to copy Xiaomi. The classic smartphone maker (OEM) business model is no longer sustainable.

Among smartphone makers, only Apple and Samsung reap significant profits. In 2014 Apple claimed 79 percent of the smartphone industry’s profits, Samsung 25 percent and LG 1 percent, according to the investment bank Canaccord Genuity. Most of the other major smartphone companies either broke even or lost money in 2014. (Xiaomi wasn’t included in the Canaccord Genuity analysis.)

Apple, as usual, is a special case and in a category of its own. Its method of firmly controlling and integrating all aspects of the iPhone, from the device’s hardware to its cloud services, gives it a unique competitive advantage in the smartphone market. Apple’s market power is evident in everything from its record market capitalization, which is currently more than double that of any other publicly traded U.S. company, to its record iPhone sales (74.5 million units in its fiscal 2015 first quarter).

UNSUSTAINABLE BUSINESS MODELS

However, Samsung is a more typical smartphone OEM than Apple – and it is losing its edge. For years, Samsung got a boost from being a huge conglomerate that built both smartphones and smartphone components. But supply chain advances have made it easier for other companies to source sophisticated components and produce competitive handsets. This development has hindered Samsung’s ability to charge premium prices for its phones and weighed on its operating profits, which have declined for five consecutive quarters. During that period, Samsung also lost its smartphone sales lead in both China and India -- the industry’s two most important growth markets.

Other smartphone makers are in an even worse position. While these OEMs now have access to enough components to compete with Samsung, they are forced to buy many of their components at higher, off-the-shelf prices. In addition, the industry’s average smartphone selling price keeps declining and is now below USD 300 (unsubsidized). Samsung and OEMs like Sony and HTC are getting squeezed at both ends as they lag Apple in premium phones and get lapped by Xiaomi and other Chinese handset makers in cheap phones.

LIKE THE BLIND MEN AND THE ELEPHANT

Unfortunately for these OEMs, copying part of Xiaomi’s business model cannot reverse these industry trends. Consider the Indian parable of the blind men and the elephant. In this centuries-old story, six men who have never seen an elephant touch one to deduce what the animal looks like. But since each man touches a dissimilar part of the elephant – its trunk, its tusk, its ear, its leg, its stomach, its tail – each comes away with a contrasting idea of the animal’s appearance.

Like the men in the elephant parable, Xiaomi copycats only see part of the picture.

The real picture is that Xiaomi’s business model is an amalgam of a strong brand, online distribution, on-demand supply management, social marketing and keen design sense.

Each part of Xiaomi’s business model is also tightly integrated with and supportive of the others. For example, selling smartphones on its own site lets Xiaomi forge direct relationships with its users. Making its own operating system software (ROM) and regularly updating it also helps Xiaomi build a following. Both tactics entice people to keep returning to the company’s website and discover new products. Xiaomi recently said that a whopping 40 million users are active on its online forums and that those users create as many as 500,000 new posts a day.

XIAOMI'S TRIBAL BRAND

Xiaomi’s enthusiastic users operate much like a tribe, as defined by Seth Godin, the noted marketer. Godin describes a tribe as a group of people who are connected to one another, to a leader and to an idea. Because tribes are composed of true fans, who act as evangelists for their leader and their governing idea, Godin says they are “bigger than word of mouth” in terms of marketing influence.

Each time Xiaomi sells a smartphone, it is recruiting a tribe member who will strengthen its burgeoning e-commerce business.

Xiaomi plans to leverage this direct relationship with users to make profits selling a wide range of gadgets, including Internet of Things, IOT, devices.

SEEDING AN IOT ECOSYSTEM

Though Xiaomi isn’t widely viewed as an IOT company, its recent investments, launches and public comments indicate that it is building a vast distribution channel for IOT products. In December, Xiaomi invested about USD 200 million in Midea, a China-based maker of air conditioners, refrigerators and washing machines. Xiaomi said the deal would lead to joint initiatives in “smart home initiatives and electronic products”. Around the same time, Xiaomi invested an undisclosed amount in Misfit Wearables, a California-based maker of wearable computing products, such as fitness and sleep monitors.

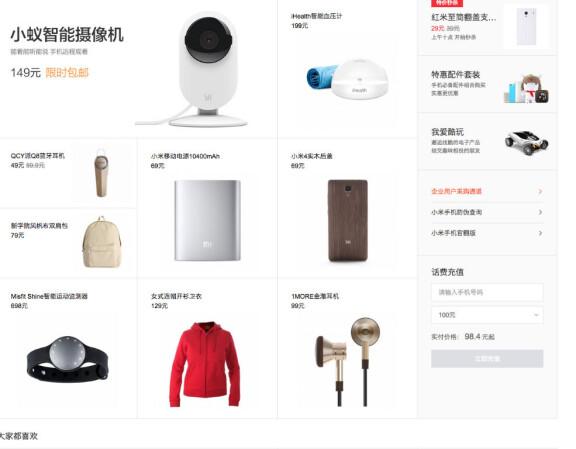

Xiaomi also sells a collection of “intelligent hardware” on its Mi.com website. This ever-growing lineup of IOT gadgets includes a blood pressure monitor and an air purifier. Both devices can be remotely controlled by Xiaomi smartphones and are joint initiatives with other companies (Silicon Valley’s iHealth Labs and China’s Zhimi Technology, respectively).

Basically, Xiaomi is using smartphones as a distribution channel for other goods and services instead of looking to smartphones as a profit source, as Apple and Samsung do.

Put another way, Xiaomi first sells a consumer a smartphone, at very little profit. Later, when the consumer has acquired more money and a larger home, Xiaomi will try to sell him a full range of smartphone-connected appliances, at greater profit. Lawrence Li, a China-based writer and podcaster, has discussed this idea in depth on Medium as has technology analyst and writer Ben Thompson, on his blog Stratechery.

THE OEM REMEDY

Where does Xiaomi’s industry shift leave a “classic” smartphone OEM? One option is to help companies and organizations build and engage communities of fans by launching their own smartphones and mobile services. Entities such as sports teams and entertainers that have large, committed groups of supporters might want to release branded phones and software – not necessarily to generate big profits selling phones, but to deepen their connections with their fans and enhance their core businesses. Smartphone makers can address multiple niche markets by providing celebrities and sports teams with ready-made mobile engagement systems consisting of phones, apps and cloud services.

Like Xiaomi, these smartphone makers would be treating smartphones as a distribution channel. The difference is that the OEMs would serve as the engines behind the distribution platform while their partners would handle the branding and marketing. This strategy enables OEMs to take advantage of Xiaomi’s third wave of disruption despite lacking “tribes” of their own.

AMAZON'S IOT PLAY

Meanwhile, Amazon is pursuing an IoT business that bears watching. In 2013, Amazon’s Amazon Web Services (AWS) division started building an ecosystem of IOT firms. Through AWS, Amazon offers IOT companies – many of which are quite small – back-end support in the form of computing power, big data analytics and security software. Amazon also helps these companies sell and distribute their wares through its online marketplace. So, while Xiaomi seeks widespread distribution by selling inexpensive smartphones, Amazon is securing a supply of IOT gadgets that can be sold to existing Amazon clients. It is too early to compare the two approaches, but the point to keep in mind is that both Amazon and Xiaomi are constructing platforms to bring IoT devices to broad consumer bases.